A New Perspective on Social Relations – The Liking Gap

With new classes, meetings, and events, the start of a new quarter opens the door for us to meet different people and form new relationships. Here is something that may change the way you think about meeting others!

Whether it be contacting potential new roommates, reaching out to professors, talking to strangers, or chatting with friends, establishing connections can often be daunting and create thoughts of doubt, fear, anxiety, and nervousness.

Why is it that something so fundamental is the root of so much worry and uncertainty?

Psychologists and researchers from Cornell, Harvard, University of Essex, and Yale University attempted to find out and documented their results in the article, “The Liking Gap in Conversations: Do People like Us More Than We Think.”

What is the Liking Gap?

The Liking Gap is the difference between how much people think others like them versus how much others actually like them. The article found that after people had conversations, people consistently underestimated how much their conversation partners liked them.

Why does it Exist?

The Liking Gap is attributed to multiple factors, including: (1) People do not fully express themselves and hide behind a guise of politeness. (2) People inhibit their true emotions in conversations for fear of being socially rejected (3) People are too consumed in their own thoughts of self-criticism that they fail to notice signals of their conversation partners liking them.

Five Experiments

Five experiments were conducted in order to study the Liking Gap. Each of the five studies reveals unique nuances to the Liking Gap phenomena.

Study 1a: People like others more than they perceive others like them.

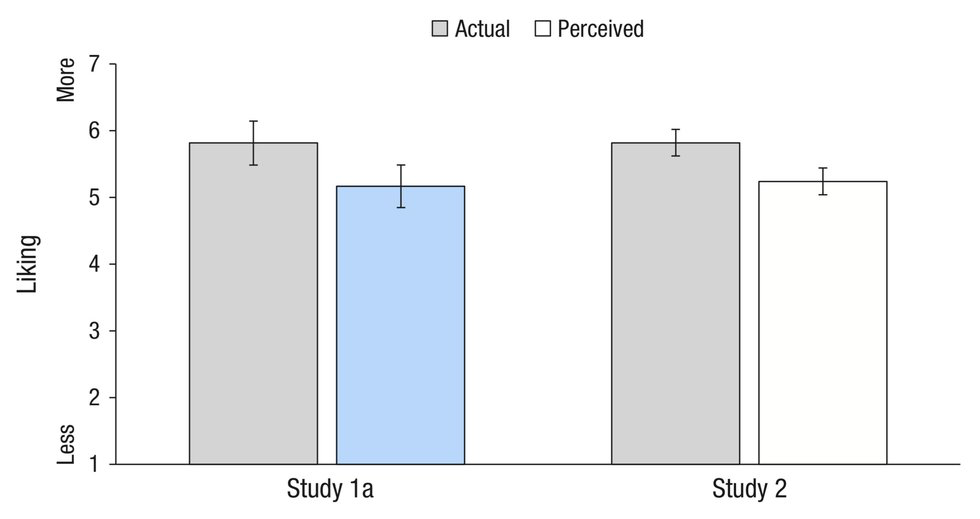

Study 1a was conducted on people of all ages from a community near Yale University. In the study, two participants were paired up and instructed to have a conversation for around five minutes. After the conversations, the participants were separated and asked questions about how much they liked their conversations partners and how much they perceived their conversation partners liked them. The results showed that, on average, participants liked their conversation partners more than they perceived their conversation partners like them. The Liking Gap is confirmed in this interaction.

Study 1b: People fail to pick up on signals showing others found them likable.

Now that the Liking Gap had been addressed, researchers wanted to figure out whether or not the Liking Gap was justified. One hypothesis attributed the Liking Gap to a neglected-signal account, where people did outwardly show signals of interests in their conversation partners, but their conversation partners were unable to identify the signals. In Study 1b, two trained research assistants observed the conversations recorded in study 1a. The researchers estimated how much the subjects liked each other, based solely on the videos of the conversations. The results revealed that the researchers’ observations aligned with how much participants reported actually liking each other. Their observations, however, did not align with how much participants perceived others liking them. Study 1b supported the neglected-signal hypothesis of the Liking Gap. Even though physical signals indicating likability were shown , people were unable to pick up on the signals.

Results of Studies 1a and 2: mean ratings of actual and perceived liking of conversation partners. From Boothby et. al. 2018.

Study 2: People are too busy forming negative thoughts about themselves to notice how much others like them.

Study 2 tried to uncover why people were missing signals from others showing interest towards them. The researchers hypothesized that participants were too consumed in their own thoughts that the participants were unable to pick up on signals from others. In the study, participants recruited from Yale University were instructed to converse for approximately 5 minutes. Other than assessing how much they enjoyed conversations with direct questions, participants were also asked to form their most salient thoughts about how their conversation partners viewed them and their most salient thoughts that they formed about their conversation partners. The results indicated that people’s most salient thoughts about how others viewed them were generally more negative than their most salient thoughts about how they viewed others. Participants salient thoughts were also affected by the Liking Gap, supporting the idea that people were too busy forming negative thoughts about themselves to notice signals of likability coming from others.

Study 3: Even with longer conversations, people still underestimate how much others like them.

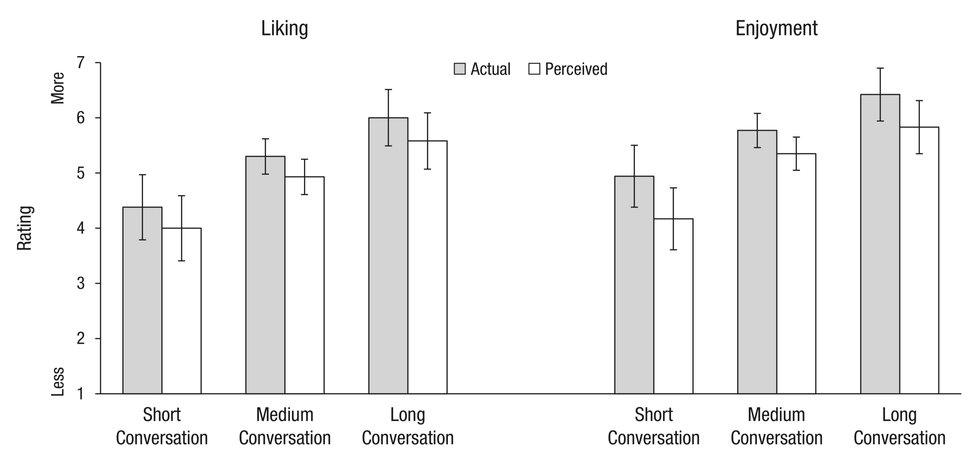

Study 3 was conducted in order to find out if the Liking Gap was dependent on the duration of conversations. Participants recruited from the Harvard Decisions Science Laboratory were instructed to have conversations for however long they wanted to and were then asked to report on how much they liked others and how much they perceived others liking them. Generally, observations showed that no matter how long the conversation, people continuously underestimated how much their conversations partners liked them and enjoyed the conversations. The study also discovered that even participants who had longer conversations reported a Liking Gap. This study proved that even in longer conversations, where people would theoretically be given more time to open up to each other, people still underestimated how much others liked them.

Study 4: The Liking Gap exists outside the lab.

Since studies 1-3 were conducted in laboratories, the authors decided to conduct Study 4 at a public event to see whether or not the Liking Gap could be observed in natural settings. For the experiment, the investigators observed strangers who attended “How to Talk to Strangers” workshops. People were instructed to find a conversation partner and spend five minutes introducing themselves to others. Both pre-conversation and post-conversation questionnaires were given. The study revealed that pre-conversation, participants predicted that they would find their conversation partners to be more interesting than them and post-conversation, participants confirmed their initial thoughts and reported that their conversations partners were more interesting than them. The study highlighted how the Liking Gap persisted in natural settings.

Study 5: In college freshmen, the Liking Gap persisted until around May, when roommates move out or continue living together.

The last study was conducted on incoming first years to college, who were instructed to take five surveys over the length of the academic year. Through similar techniques and analysis, the researchers were able to find that the Liking Gap persisted between roommates in the first four surveys, from initial meeting in September to around February. In the last survey, however, which was taken in May, the Liking Gap ceased to exist and there was no underestimation in how much participants believed their roommates liked them. Researchers attributed the absence of the Liking Gap in the fifth study to the fact that roommates would be forced to have conversations about potentially rooming with one another for next academic year and uncertainties about whether or not people actually liked each other would be brought up to the surface.

Results of Study 3: mean ratings of actual and perceived liking (left) and actual and perceived conversation enjoyment (right), separately for participants who engaged in short, medium, and long conversations. From Boothby et. al 2018.

Why is this important?

When people cannot comfortably express themselves, they leave conversations uncertain whether their conversation partners truly enjoyed their presence. This insecurity decreases their likelihood of connecting with that person again. The Liking Gap creates a barrier to forming new connections with others and reinforces overly self critical tendencies.

Acknowledging the Liking Gap can help us resist its impact on forming meaningful social connections. Think of all the relationships that could have been created had it not been for the Liking Gap. Our mistaken beliefs about people we have conversations with should not deter us from meeting people who have the potential to be great friends and mentors.

Because of the Liking Gap, we are often too caught up in our own thoughts of “oh, do they like me?” and are not present enough in the conversation. We are unable to provide our conversation partners with our attention and express ourselves fully. The Liking Gap shows us how pervasive negative thoughts can be and how they may affect our conversations and relationships.

Most importantly, understanding the Liking Gap can help us change the way we interact with others. The Liking Gap does not have to exist. We have the ability to recognize this pattern and recognize when we are limiting ourselves from more meaningful connections with others.

What should we do now?

As part of EngageWell, our mission is to promote social connection and foster greater social well-being in students staff and faculty. We encourage you to think about ways the Liking Gap may have kept you from creating meaningful relationships. Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Start a conversation around the Liking Gap. I shared some of the findings in this post with my friends and many were extremely interested in the topic could relate to the experience.

- Reach out to someone you don’t know – professors, peers, TAs, faculty. You’ll be surprised at how differently you approach conversations without reservations of uncertainty

- Find someone that you initially had reservations in approaching and strike up a conversation. Do not let your fear of not being liked stop you from approaching potential friends!

The full article if you are interested:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797618783714

Jessica Yang is a second year student majoring in Environmental Science with a concentration in Environmental Health. On top of blogging for Semel HCI, she is part of club swimming and hopes to pursue a career in healthcare in the future.